Protectionism: Between its Proponents and Detractors

Smart, limited policies that help maintain the U.S.’s economic edge, safeguard its national security, and strengthen supply chains, all while minimizing trade disruptions.

At the recently held State of the Union Address, President Biden celebrated a policy that would ensure federal infrastructure projects were built using materials made in the U.S.:

Tonight, I’m announcing new standards to require all construction materials used in federal infrastructure projects to be made in America.

It was one of only a few statements that received a bipartisan standing ovation that night, and it’s good politics. Many economists and policy experts, however, weren’t as convinced by the rule, which is argued to lead to higher costs in a country fast becoming infamous for its expensive government-funded construction projects. Protectionism is nothing new, and the economic case against it is strong. But its critics are often too quick to dismiss even moderate forms of it, and current history shows why this can be a mistake.

The economic argument against protectionism is that it’s inefficient. If countries restrict international trade then consumers face higher prices, producers have access to fewer markets, and everything is generally more expensive. “Buy America” policies increase the cost of construction, and direct subsidies mean fewer funds for anything else. Instead, countries should specialize according to their comparative advantages and trade.

And these are great, well-supported arguments. If you’re reading this expecting a case for blanket autarky, then I’m sorry to disappoint you. And in an abundance of clarity, I will go as far as saying that protectionism is mostly bad economics, and I generally align with the consensus on this topic. What I’m actually advocating for are smart, limited policies that help maintain the U.S.’s economic edge, safeguard its national security, and strengthen supply chains, all while minimizing trade disruptions.

The passing of the CHIPS and Science Act — which commits federal funds to bolster the semiconductor industry and science research and development more broadly — is a great example of an excellent protectionist policy. Semiconductors are a part of nearly every electronic device including computers and advanced weapons, and as such, the development and manufacturing of them is not only an economic concern but a geopolitical one as well. Without semiconductors, an F-22 fighter jet could not effectively shoot down a balloon, or anything else for that matter. Artificial intelligence depends on this material and it could become more commonly used in quantum computers in the future. The world as we know it is shaped by tiny components that utilize semiconductors.

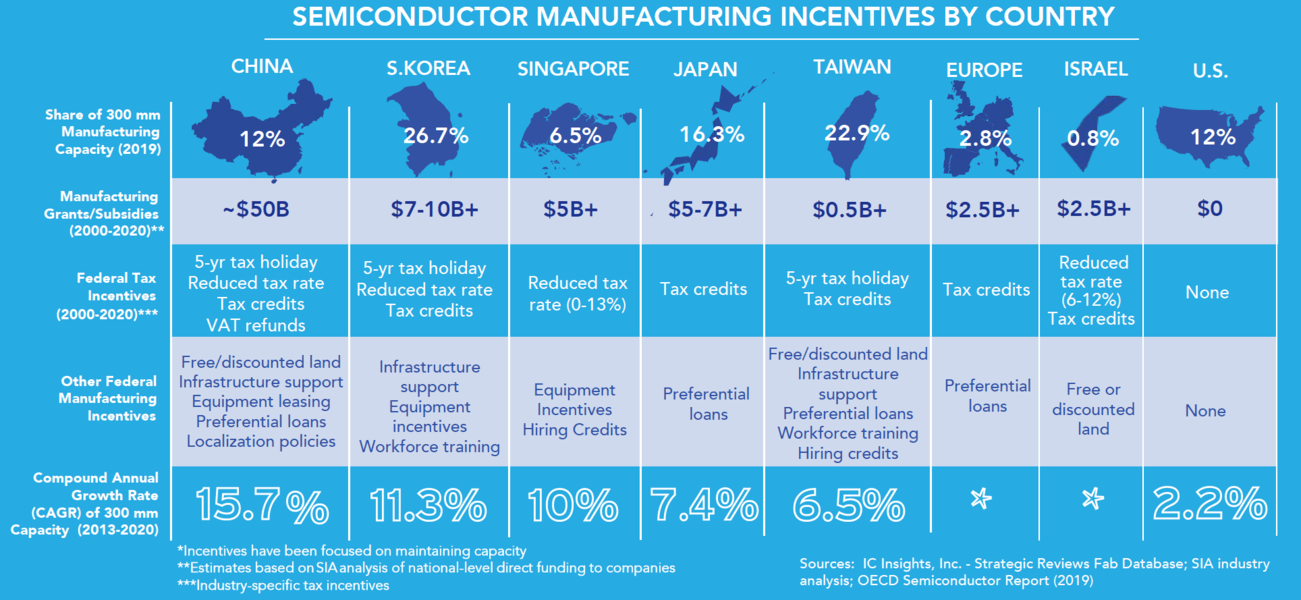

Prior to CHIPS, the U.S. offered no semiconductor manufacturing grants or subsidies and no other forms of federal incentives. The European Union, Japan, and other chip-producing countries, on the other hand, did. China spent an estimated $50 billion in grants and subsidies from 2000 to 2020 along with other incentives, and it’s committing billions more to construct more fabrication plants and increase its manufacturing capacity.

In its 2021 State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry report, the Semiconductor Industry Association wrote:

While the U.S. industry leads in R&D intensive activities, Asia leads in manufacturing process technology, supported by government incentives. When it comes to leading-edge logic capacity below 10 nanometers currently in operation, none is done in the United States. The United States is also well behind as a location for logic capacity 28 nanometers and above.

Now, the U.S. is providing $52.7 billion for semiconductor research and development, manufacturing, and workforce development, which includes $39 billion in manufacturing incentives. The CHIPS bill also provides a 25% tax credit for capital expenses related to chip making, and it authorizes $174 billion to invest in STEM education and training and research and development.

The United States has a competitive and comparative advantage in drawing and developing human capital, and in the industries that result from that. The U.S. has the world’s best universities and it attracts more immigrants than anywhere else. People have been, and are, the country’s greatest superpower. The American Dream isn’t an American concept — it’s a human one. It’s just that the U.S. embodied this idea in a way that other places didn’t.

“... Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

The embossed words of Emma Lazarus on the Statue of Liberty now seem to invite more cynicism than they do hope, but I contend that this idea remains a core ethos of the United States, and that it’s key to its economic success. And in order to exemplify this, the U.S. must invest in the industries and technologies that make it the most attractive place to work and live. Given the importance of semiconductors to the global economy and to national security, it’s critical that the country’s ability to produce them does not diminish, and that its role as a major semiconductor innovator is not ceded to other countries who want it more.

This new commitment to chips and science, however, was not what drew the most criticism during Biden’s address to the nation. By that time, CHIPS was touted as a win for the Biden administration and Congress, and my impression is that its passing was generally well received by economists despite it falling under the scope of protectionism. It was the zeal for the Build America, Buy America Act included in the $1 trillion bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that continued to raise eyebrows. The new standards tighten existing “Buy America” policies as Livia Shmavonian, Made in America Director of the Office of Management and Budget explains:

The law, which includes the Build America, Buy America Act (BABA), significantly expanded these standards to require that federally funded infrastructure projects use American-made iron, steel, construction materials, and manufactured products. …

This includes domestic manufacturing process standards for each construction material referenced in the [Bipartisan Infrastructure Law], including plastic and polymer-based products, glass (including optic glass), lumber, and drywall.

One of the most common arguments in favor of “Buy America”-style protectionism is that it’s a boon for domestic jobs. Surely by supporting key industries, you will also support the jobs in those industries. But this doesn’t account for jobs in the entire economy that are affected by consumers having less money due to higher prices for goods from protected industries, and higher prices that firms need to pay if a protected industry produces a crucial input. Both of those effects lead to lost jobs or slower job growth in other industries. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics:

We calculate that the annual taxpayer cost for each US job arguably “saved” by Made in America probably exceeds $250,000. We put “saved” in quotation marks because buy national requirements essentially shuffle jobs from other sectors of the economy to the procurement sector. And the shuffling takes a toll on economic efficiency, which shows up in elevated price tags on everything from computers to bridges. On balance, buy national requirements create no new jobs, but they do save jobs in domestic firms that supply government needs, often at a high cost to taxpayers.

So I’m not going to defend policies like this on the grounds of job growth in the economy. As it relates to construction materials specifically, the benefits are instead in the form of supply chain resilience and national security.

In the 2022 annual report of the Council of Economic Advisers, White House economists wrote that “supply chains have become more complex, interconnected, and global than they were in decades past,” and they acknowledged that this has been beneficial to both the American and the global economy:

This increasing segmentation of the production process has reduced prices in the United States, while also raising productivity and aggregate incomes in many of the low-income countries that are integral to global supply chains.

But they go on to explain how an overreliance on that interconnectivity has resulted in less resilient supply chains, the vulnerabilities of which were exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine:

The globalization of production has also made supply chains more vulnerable to disruption. …

Because of outsourcing, offshoring, and insufficient investment in resilience, many supply chains have become complex and fragile, with central nodes that lack agility and have few substitutes.

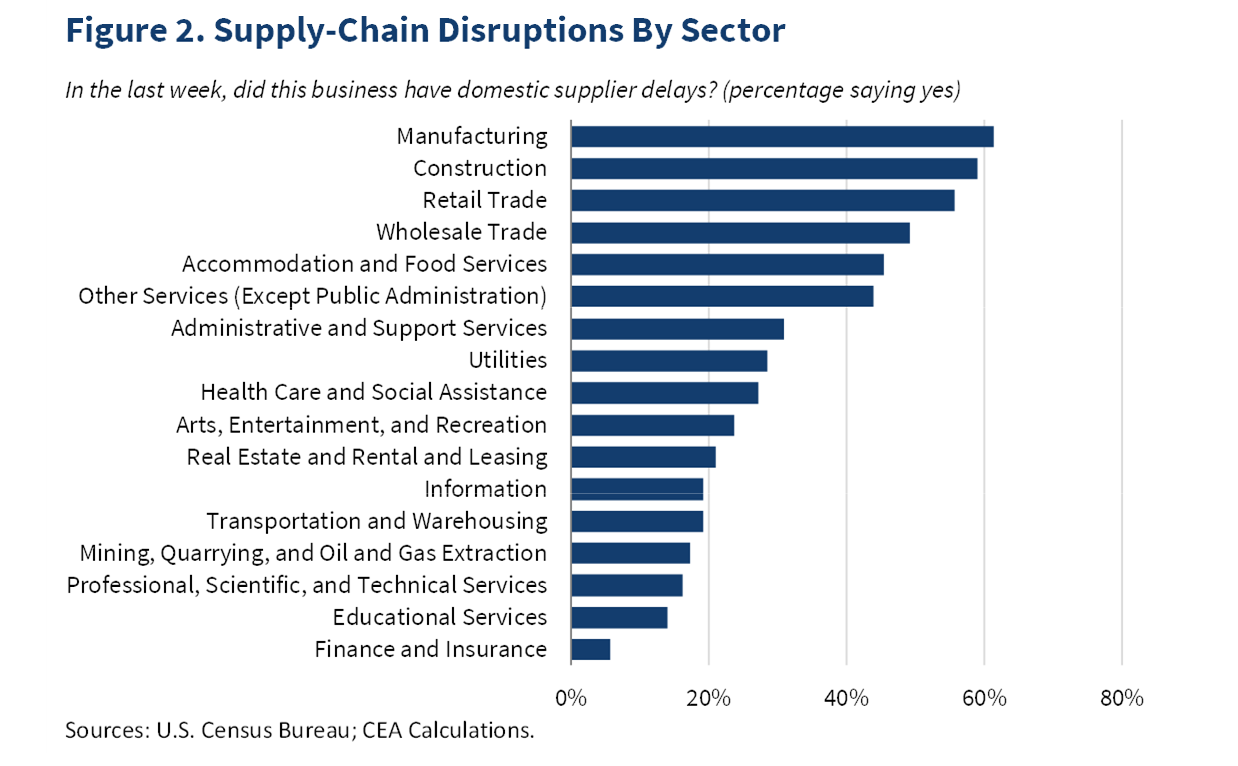

The Council of Economic Advisers posted this graph along with a blog post in June 2021 during the peak of the supply-chain shortages. It shows that around that time nearly 60% of businesses in the construction sector reported having domestic supplier delays in the last week.

Shocks to the global economy would impact a country’s domestic industries less if they were able to rely more heavily on domestic and nearby suppliers. The U.S. could produce, for example, more steel and lumber, and favor countries close by when importing those goods in a process known as on-shoring and near-shoring, respectively. And to some degree this already happens naturally. The top countries that the U.S. imports its steel from are Canada and Mexico, not China and Russia. To state the obvious: shipping costs increase as whatever is being shipped gets farther and heavier, so it makes sense to try to minimize transportation times when importing something like steel.

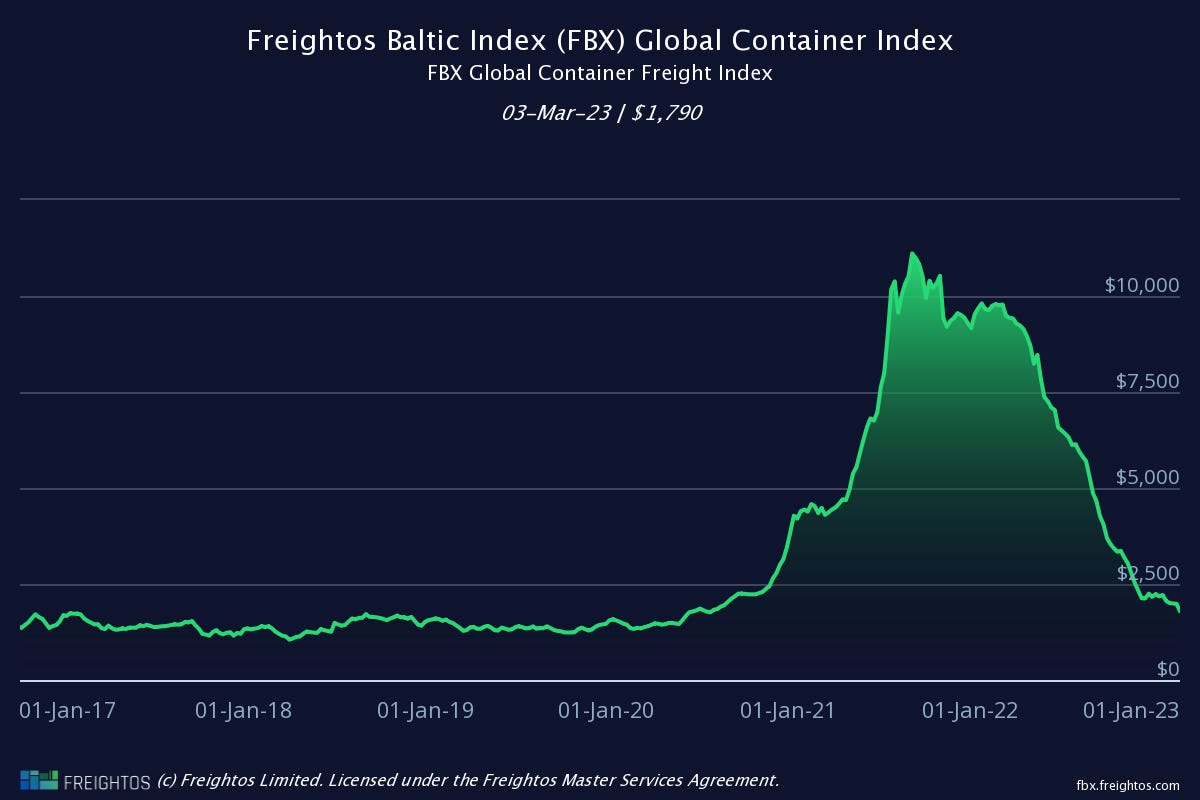

Shipping rates were significantly elevated during the pandemic as consumer demand remained strong and ports were hit with lockdowns and labor shortages. Those high rates showed up in goods prices and contributed to inflation. While the U.S. often chooses to import from countries next door when it can save on shipping costs, it still imports a significant amount of goods from farther away, and distance and geopolitical tensions mean that sprawling supply chains are more susceptible to disruption.

The benefit of protectionist policies to national security is more self-evident than it is particularly quantifiable. If some devastating global catastrophe or a major war should befall the U.S., the country needs to be able to produce the goods and services necessary to sustain itself. National security is a public good that will be undersupplied if not for society (i.e., the government) stepping in to provide it. If a certain level of self-sufficiency is required to stave off the worst disasters, then national security in this case is not merely the military and government agencies, but it’s also the resources they depend on. Now whether or not any given policy actually achieves its stated aims can certainly be debated, but any policy that guarantees sufficient domestic production would be considered protectionism, and that’s not reason enough to reject it outright.

When it comes to “Buy America” policies, I find myself somewhere between the supporters and the detractors. The increased stringency of the Build America, Buy America Act is probably overkill, but I also recognize the need for something that protects the U.S.’s critical domestic industries. Policy makers have the unenviable job of ensuring a robust and competitive American economy while avoiding unnecessary costs, construction delays, and disincentivizing innovation. This means embracing some forms of protectionism and making sure it’s done right.